First published 1993

Revised and expanded 2000

APPENDIX 1: An 1854 Reading-Examination Sermon of

L. L. Laestadius

APPENDIX 2: A Sermon of L. L. Laestadius Given on

the Fourth Sunday after Easter in 1851.

APPENDIX 3: A Sermon of L. L. Laestadius Given on

the Fourth Sunday after Trinity in 1851

APPENDIX 4: A Sermon of L. L. Laestadius Given on

the Sixth Sunday after Trinity in 1859.

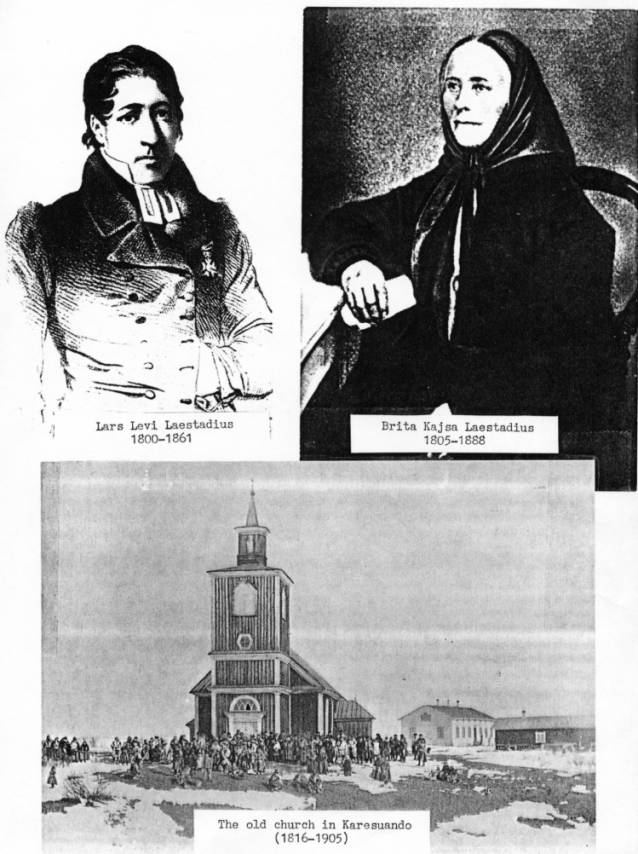

Lars Levi

Laestadius was born on January 10, 1800, in a remote, desolate region of

Swedish Lapland. The site, known as Jäckvik, is on the western end of

In his autobiography,

Laestadius has described his father Carl as cheerful and playful, except when

he had been drinking.[1]

Obliged to leave his low-paying job as superintendent of the Nasa Silver Mine,

a failing enterprise, Carl Laestadius tried to eke out a living from the land

with his first wife, a city woman from

At fifty years of

age, after the death of his first wife, Carl married Anna Magdalena

Johansdotter, a forty-year-old widow from Sorsele. With this country woman, he

moved to Jäckvik and made a second attempt to earn a living as a settler.

However, he was away much of the time, at least in the winter, selling his scant

produce and buying supplies. Lars’ younger brother Petrus has aptly commented

in his memoirs that their father, who was accustomed to being among people,

“did not have any

In his autobiography, Lars tells of his “melancholy” mother, who had to “pay in bitter tears” for her husband’s drinking but was never heard to complain over her harsh fate, “for she bore her cross with patience.” He goes on to describe how he was named: “While pregnant she dreamed that a little boy named Levi was running after her husband, and she marked this name in her memory. When the child was about to be born, she dreamed again, while in labor, that someone shouted, ‘Lars.’ Born healthy, the child entered the world in a cold, wretched cabin. When the mother recovered, she had to bear the child in her arms to the pastor, who lived about 40 miles from her home. There the child, whose name had been revealed in a dream, received in baptism the name Lars Levi.”[3] Laestadian legend expands on this account with the story of the mother carrying the baby to the church in a birchbark basket on her back, in the manner of the Lapps. It is told that on the way she was caught in a snowstorm and found in a snowbank by a Laplander’s dog, which saved her by barking for help. Petrus Laestadius says, however, that it was he, rather than Lars, who was carried about six miles from Buokt, where the family settled after spending less than two years in Jäckvik, to Arjeplog to be baptized. He says that “for easily understandable reasons this could not be done with Lars Levi,” who received an “emergency baptism” in Jäckvik. The accounts can be reconciled when it is understood that, in any case, the mother would have had to take Lars to the church for confirmation of such a baptism later in the year.

Petrus was born on February 9, 1802. A year later the family moved from Buokt to Arjeplog. Petrus describes the poverty that followed them: “At that time all the settlers were in great want, and only a few could be said to have their daily bread. Their children were reared in extreme poverty and indigence, but there were none in the whole parish as despised and ragged as we. We were the most lowly of all, and no one wanted to acknowledge any relationship with us.” He also tells how, in order to sustain two cows and a few sheep and goats, their mother had to gather hay with a sickle or by hand from between rocks and from marshes. The boys had to be tied down while she worked outside because, once, Lars had accidentally poured hot ashes on his brother and then hid in fear of punishment. He was found outside in the dark, lying on the ground crying.[4]

Carl Erik Laestadius, a half brother of Lars and Petrus had, in the meantime, worked his way through school and was ordained to the ministry in 1803. Assigned to Kvikkjokk in 1806, he invited his father to bring the family there in 1808. Lars and Petrus had already been taught to read at home, mainly by their mother. Their father had taught them to recite morning and evening prayers. They were also able to give simple answers to questions regarding the articles of faith. Now, with Carl Erik as their teacher, the boys received an education that qualified them to enter secondary school.

During childhood, Lars saw certain visions, which he describes in his autobiography: “I saw as though in a dream that a woman was sweating blood over Christianity. This woman aroused in me intense sympathy, an amazingly exalted sense of reverence and admiration. It was a majestic spectacle, but I did not feel worthy to participate in her martyrdom. The woman was as though in a seated position. She endured her suffering with a courage and patience that made me marvel. I have never forgotten this sight, but who this woman was, who sweat blood over Christianity, has not yet become clear to me. Early in my childhood, I also smelled the strange odor of a dead body in the woods, and this occurred often. I conclude that it was actually a spiritual odor because my dreams often involved dead people. They greatly beset me, but I obtained a remarkable power to fly high over the earth so that they could not harm me.”[5]

Laestadius believed that the visions of dead people signified an “internally dead condition.” He explains: “The recurring odor of death and the struggle with dead people were undoubtedly a reminder, a premonition, of spiritual and eternal death, but the flight that freed me from the deathly agony was a mysterious indication of a higher power. Although these dreams came in the form of clear images and caused a certain anxiety even while awake, the impression they made did not last long. At times I tried to connect these premonitions of a higher world with my internal condition, but I couldn’t achieve any clear insight into my inner life.”[6]

Laestadius describes an otherwise normal childhod. He says that he was quite daring when skiing in the winter and climbing cliffs in the summer. He also enjoyed playing pranks on the old Lapp women, a trait he believed he had inherited from his father.[7] However, he also says that he shared his mother’s melancholy nature. As an example, he describes an experience he had at 16 years of age. The young people of the village were at a dance. Lars enjoyed such events but this time he was not there, and so his girlfriend left to search for him in the surrounding buildings, including the parsonage, where he lived, asking for him everywhere. She finally found him sitting hidden behind an outhouse. She could not persuade him to go to the dance, nor could she learn the reason for his strange withdrawal from the world.

Laestadius did not attribute his behavior on this occasion solely to his “melancholy nature.” He says that he became aware of another reason for it 27 years later: “There can hardly be a person who has not been troubled at some time in his life without knowing why, but there are very few who heed that mysterious inner voice. When the written word does not cause a person to come to his senses, the Spirit of God must work directly through an inner voice to awaken the careless sinner to reflect on his condition. However, even this inner calling is often disregarded because the effects of grace of God’s Spirit are not recognized. Often, people who have been warned by such a voice view it as an omen of great impending misfortune, that either they or close relatives are near death, but it does not occur to them that this inscrutable and inexplicable depression, for which there is no outward cause, must be a reminder from God’s Spirit for people to reflect on their spiritual condition.”[8]

Lars and Petrus

were admitted to the secondary school in Hernösand in 1816. Though beset by

financial difficulties as a result of Carl Erik’s death from tuberculosis the

following year, they were successful in their studies. Lars was particuarly

interested in botany and made trips as far as

Laestadius says

that during his school days he was scorned because of his poor clothing and was

excluded from the world’s clubs and activities.[10]

Later in life, however, he was recognized as an expert in the vegetation of

As a student, Lars

maintained high moral standards and was highly respected by the girls with whom

he associated. He says in his autobiography that he engaged in the practice of

bundling, adding that, in spite of how incredible it may sound to the

“whoremongers of

Having completed

secondary school, Lars and Petrus moved to

One day in

After serving

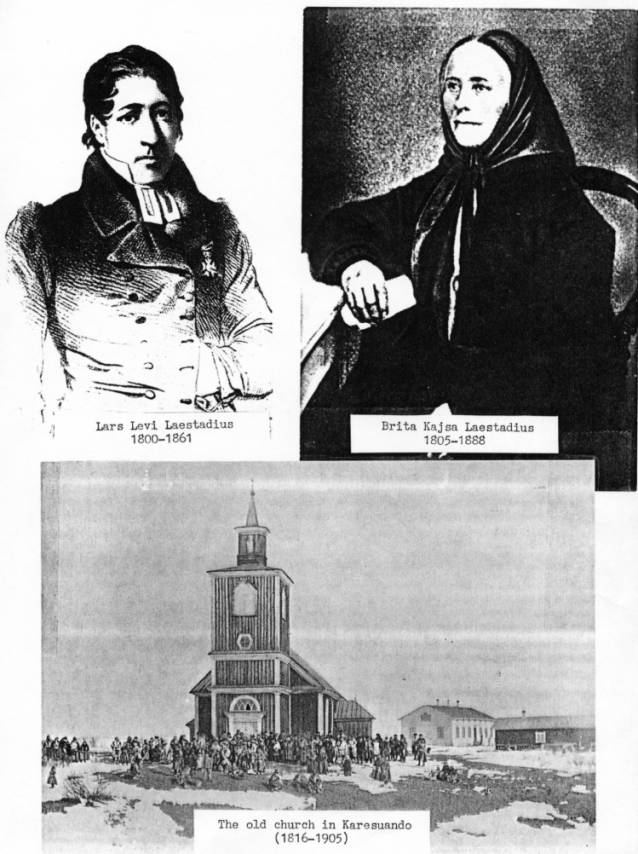

briefly as assistant pastor of Arjeplog and missionary to the Lapps, Lars began

his ministry in Karesuando in 1826. The position of pastor in this harsh

region, inhabited by nomadic Lapps and Finnish settlers, had no redeeming

qualities. The salary, which was the lowest of any pastor in

In spite of his own dead spiritual condition, Laestadius sought a wife who was “gentle, humble and had experienced grace,” one who “from a spiritual standpoint, was marked by mild fanaticism.”[15] He felt that such a woman could not be found in refined circles. Finally, he decided that a woman by the name of Brita Kajsa Alstadius, a settler’s daughter from the area between Arjeplog and Kvikkjokk, came closest to his high ideal, and they were married in Karesuando in 1827. He wrote 25 years later that this period seemed to be “the only reality in life’s dream; all other joys of life have vanished, leaving only a dim memory of what is past.”[16]

Laestadius went to great lengths to teach the Lapps to read, visiting their tents, for example, to give them reading examinations. His confirmation classes lasted four weeks, and those who could not read were not admitted to communion. His main concern, however, was over the liquor trade and its consequences. Men abused their wives. Children went unattended while their mothers lay in a drunken stupor. Families were drained of their resources, selling even the clothes off their backs for liquor. The state was well aware of the disastrous effects of the liquor trade but its prohibition decrees went unheeded.

It was apparently

during the winter of 1832-33 that Laestadius came down with what he believed to

be typhoid fever and gave up all hope of recovery. His concern at that time was

not over the fate of his soul but over the welfare of his family. He explains:

“I had always believed that God is good. I had always been convinced that God

provides for our earthly subsistence. Now this faith in

Laestadius recovered, and in 1836 his wife gave birth to the twins Levi and Elisabeth, the fourth and fifth of 12 children. In 1839, however, Levi died of measles. The mother, who was also ill at the time, did not appear to be as deeply affected as the father. In the words of Laestadius, “she counted herself fortunate to have been viewed worthy to bear fruit for the kingdom of heaven.” As for him, however, the death had a deep and lasting effect, which was reinforced later, when he again fell ill. He comments: “A man indeed needs some reminders of his mortality. Otherwise, he will entirely forget the purpose of his existence on earth. Levi’s death was such a reminder, but I had an even stronger reminder in 1842, when pain in my chest led me to think that I had tuberculosis, which would inevitably end in death. This thought then took hold of me: ‘Set thine house in order, for thou shalt die’ [Isaiah 38:1]. Now, for the first time, I had a serious and deep fear of death.”[18]

Laestadius thus came to true awakening, that is, he was made aware of his dead spiritual condition, as he says, “For me the fear of death was an eyesalve. My eyes were opened to both the past and future. I saw the consequences of my ungodly life facing me in eternity, for, on the whole, my life had been more ungodly than godly, even if, in the eyes of the world, I could have been considered a model of virtue. All the sins of my youth now came into view before me. Afterwards, I have wondered how all these deeds were as though forgotten until this fear of death appeared. It couldn’t have been anything but dead faith that had concealed them until then, and what else but the same dead faith could have prevented all fear of death from appearing ten years previously when I was close to dying? At that time I thought I was prepared to die, but ten years later, plagued by this illness in my chest, I was totally unprepared to die.”[19]

Laestadius also

became concerned over the spiritual condition of his congregation. He

continues: “I only recall that from that time I was drawn, as though forced by

a higher power, to feel, think and act directly against my own will, and thus

my awakening and that of others is not a work of my own will. Even if the world

should say that it is a work of the devil, as the Jews and heathen believed

about Christianity, I know in my own conscience that it is not my own work. My

own will and my own evil nature have been as reluctant as was Moses when God

ordered him to lead the children of

Recovering from

his illness, Laestadius began to preach more sharply against drunkenness. A new

prohibition law, which established a heavy fine for the import, sale or

consumption of hard liquor in

The constable

ignored the law, for, as was pointed out by one pastor of the time, a swig of liquor

was the “hub around which the life of

In the fall of 1843, Laestadius, seeking a new position as pastor of Pajala, traveled to Hernösand, to take the required pastoral examination. He says that when he arrived in Hernösand he was still viewed as an “orthodox Lutheran.” There, however, he published a Latin work that lamented the low moral and spiritual state of Swedish society and caused him to be viewed henceforth in a different light. The translation of the full title of the booklet, referred to generally only as Crapula mundi (the world’s intoxication), is the best description of its contents: “An examination of the world’s intoxication or the contagious disease of the soul, whose cause is hidden, under the guise of liberty, in moral bondage, with visible symptoms appearing in the turbulent agitation of nations and woeful end of spiritual death, together with applications to the life-styles of all social classes.” In Hernösand, he enjoyed listening to the preaching of Pastor Pehr Bylund, who was known as a reader and wondered why this man, who did not “wound” the human heart but only “pricked it with the truth,” was so hated.[25]

Under the

Conventicle Edict of 1726, the laity could not hold religious services or

preach in

Petrus Laestadius,

who came into close contact with the readers

after being assigned to Piteå as a missionary to the Lapps, refers

sarcastically to them as “champions of faith,” saying that the “whole

fanaticism is really based on misunderstood writings of Paul and Luther” and

that, “instead of the mild, philanthropic and peaceful doctrine of Jesus,” the readers have a “most intolerant and

contentious fanaticism, full of arrogance and spiritual pride, which almost

hates the very name of virtue and Christian conduct, and, under the

misunderstood slogan of salvation by

faith alone, dashes blindly over all limits of social order, modesty and

sensibility.” Petrus admits, however, that in conduct the readers were irreproachable. He says, for example: “In Kvikkjokk

there is a large village, or rather family, by the name of Sirkas, which

together with Kaitom in Gällivare, was the most uncivilized and barbaric in

Petrus was frustrated by the attitude of the readers toward the state church, from which some had begun to separate. He writes: “If you enter into a discussion with them, they only preach and scream their old routine at the top of their lungs, never listening to what you say, and the one who screams the loudest and holds out the longest is usually the greatest prophet in the eyes of the uneducated crowd.” Petrus was particularly offended because they condemned “the pastors and their doctrine and all who heed them to the pit of hell.”

The readers were a heterogeneous lot. There were not only the pietistic old readers and the more evangelical new readers, but the latter also disagreed among themselves on various issues. In fact, anyone who took a serious or unique approach to religion, whether Lutheran, Methodist, or Baptist, conformist or separatist, eventually became known as a reader. Petrus continues: “In Arvidsjaur, an anti-reader approached a leader of the readers, pretending he was becoming one himself. The following conversation took place between them: Anti-reader: ‘I am a terribly great sinner. I am unable to improve.’ Reader: ‘It doesn’t matter as long as you believe.’ Anti-reader: ‘Yes, but it is so dreadful. I have such a desire to steal.’ Reader: Steal freely. It doesn’t matter. We have One who has settled accounts for us and has also acquitted us.’ Anti-reader: ‘Yes, but I have such a desire to commit fornication.’ Reader: ‘Go ahead, it doesn’t matter.’ Anti-reader: ‘Yes, but still worse, I want to commit arson.’ Reader: ‘Burn freely, it doesn’t matter as long as you believe.’ Anti-reader: ‘Yes, but it is precisely your house that I have been thinking of setting on fire.’Reader: ‘Come now, good fellow, that changes things!’ Then the anti-reader dropped his mask and told the reader what a scoundrel he was for encouraging all kinds of vices and crimes as long as they didn’t affect him. Once, an avid reader entered a house where people were gathered and said in a genuine reader tone, ‘I have the keys of the kingdom of heaven.’ Then one of those present said, ‘If you have them, you have indeed stolen them.’ It should be noted that the man really was known for having, as they say, long fingers.”

“Many readers,” Petrus writes, “even claim to

be Christ himself. In Råneå, there is said to have been one such reader-Christ, who had the saying ‘I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and

the end’ [Revelation 22:13] embroidered in large letters on his clothing. In

Arvidsjaur, there still exists a Christ,

but his fanaticism is so peculiar that it does not appear to have any

connection with readerism. His creed

is, moreover, almost simpler than that of Mohammed and consists of the

following: There are only two sins, drinking and smoking. If one refrains from

these and believes in him, he will be saved. The question is not one of strong

drink in general, for he himself drinks cognac and rum and he -- the Christ

that he is -- has been fined for drunkenness, which is rare in Arvidsjaur. He

had previously been a churchwarden, but Pastor Rhén removed him with the words:

‘Since you have become Christ, the job of churchwarden in Arvidsjaur is too

mundane for you.’ It is, moreover, characteristic of readerism to misinterpret Bible passages and to apply things,

whether appropriate or not, to themselves. When you tell readers, ‘Judge not, that ye be not judged’ [Matthew 7:1], you are

sure to hear in reply: ‘He that is spiritual judgeth all things, yet he himself

is judged of no man’ [I Corinthians 2:15]. In

Petrus evidently retained his attitude toward the readers until his death from tuberculosis in 1841. Lars, however, began to view them in a new light. In Hernösand, he was ordered to carry out an inspection tour of a number of churches and schools on his way home from the examination. After the first inspection in Föllinge, he began a two-day inspection in Åsele on New Year’s Day, 1844, just before the beginning of the annual fair, which attracted many Lapps from Föllinge. According to the record of the inspection, Laestadius asked, in the presence of the congregation, whether the clergy had detected any spiritual life in the parish. Assistant Pastor Olof Lindahl replied -- a bit too lightheartedly perhaps -- that any real zeal of that sort was rare in Åsele. When Laestadius retorted with the question of whether this lukewarmness in Christianity could be attributed to the teachers, a member of the congregation spoke up to defend Lindahl, saying that he had presented the word of truth with zeal and ardor.[28]

It was apparently

later the same day that Laestadius came into contact with a young Lapp woman,

who showed him the way of salvation. Known for over a century simply as Maria,

Lapin Maija or Mary of Lapland, she has finally been identified as Milla Clementsdotter

of Föllinge.[29] The

meeting is best described by Laestadius himself: “In the winter of 1844, I came

to Åsele,

Although it is assumed by some who consider themselves followers of Laestadius that he confessed his sins to Maria and that she freed him by proclaiming absolution, he nowhere indicates that anything like this took place. His focus is not on his own experiences -- which he may indeed have shared with her -- but on hers, and by hearing her story he saw the light. Furthermore, individual absolution was not practiced by laymen during the first six years of the revival, and if the Pastor himself had been absolved from his sins by a “simple” Lapp on that day in 1844, there could have been no subsequent discovery of the keys. The teacher Juhani Raattamaa writes about the discovery: “The spiritual movement had spread for six years already before I really understood the freedom. Since then, I and some brothers and sisters have put the keys of the kingdom of heaven into use, by which troubled souls began to be freed and prisoners of unbelief began to lose their chains, and they rejoiced in spirit.”[31] Raattamaa has also left an account of the event in Åsele that agrees with that of Laestadius: “He lived impenitent until he lost a child and feel ill himself. Then he noticed that he was not ready to die, and he became contrite. So he started to seek salvation, but he did not understand it until the Lapp girl Maria said to him that he should believe his sins forgiven in the condition in which he found himself. Then he obtained peace by faith in Jesus and began to preach by the power of the Spirit.”[32]

During his inspection trip, Laestadius became acquainted with the work of the schools established by the Swedish Missionary Society, which was viewed by orthodox Lutherans as a “fanatical” organization infected with Methodism. Laestadius, however, was impressed with the reading skills and enthusiasm of the Lapp children, who shed tears when they were separated from their teachers. In his official report of the inspection in Lycksele, he praised these teachers, “who had sacrificed themselves entirely to this cause and whose names each and every friend of living Christianity will find written in the book of life.”[33]

During the inspection in Sorsele, Laestadius again met readers, some of whom were related to his mother.[34] They were divided into two groups. After Laestadius had delivered his sermon, Johan From, the leader of one group, spoke up to complain that the pastor in Sorsele, Anders Fjellner, did not correctly distinguish between law and gospel. The leader of the other group, Pehr Königsson, a cousin of Laestadius, submitted a handwritten document for the King in which he complained that the new church handbook contained doctrines that conflicted with God’s Word and Lutheran doctrine. The two leaders apparently shared the same concern over the prevailing pelagianistic doctrine of justification, but in a discussion held the following day, Laestadius learned that they differed on other issues, such as the use of coffee, tobacco and fashions in clothing. Königsson approved, for example, of the action of Greta Mårtensdotter -- another cousin of Laestadius -- who, motivated by visions and revelations, had cast fashionable items of clothing into fire, which From, who had been present, snatched out of the fire, quoting Joel 2:13: “Rend your heart and not your garments.” He felt that it was better to sell such items and to use the money for some useful purpose.[35]

When Laestadius returned home, the change that had occurred in him became evident in his sermons, which had always been more legalistic than those of his predecessor, Zacharias Grape, though he admits that he had tried to imitate his style. He writes: “If any preacher, without awakening by the law, could accomplish any good in a spiritual respect, it was indeed this teacher, who was zealous in his own way and whom I should mention with grateful memory. He indeed tried to move the hearts of his listeners with the gospel. He made the hearts of the old peasant women melt in tears. At times, speaking extemporaneously, he milked a whole bucket of tears. It almost seemed, however, that he squeezed their soft breasts rather than their hard hearts. These tears were shed in vain in the temple of the Lord, for they dried up as soon as the listeners went out into the open air. No change appeared in their lives. Pastor Grape’s sermons were praised, but not a single word of his sermons followed them home. No awakening, no unrest, no spiritual sorrow, resulted. They drank and lived in as ungodly a manner as before.”[36]

Laestadius now “preached the law” so sharply that no conscience should have escaped, but this had no better effect than did Grape’s evangelical sermons. In fact, the temperance movement advanced somewhat, for Pekka Piltto, who had suffered a great deal of abuse for taking his temperance pledge, was finally joined by a number of other individuals, but there was no sign of any spiritual awakening. In a letter written in May to one of the Swedish Missionary Society’s teachers whom he had met on his inspection trip, Laestadius describes his predicament: “Here in Karesuando the literal knowledge of Christianity is indeed comparable to that of the Lapp peasantry of Arvidsjaur, but there is, unfortunately, no spiritual knowledge, that is, the kind based on experience. Oh, how I would like to find here some souls as experienced in the order of grace as I found in Åsele! Can you, Mr. Norberg, tell me the means by which a sinner is awakened from his stupor after he has become somewhat established in literal knowledge? The readers say, ‘Through the law.’ I have preached the law as sharply as I could, but it doesn’t have any effect. My predecessor, Pastor Grape, preached mostly pure gospel, and the old ladies blubbered in church, but there was no sign of serious repentance or new birth.”[37]

At first, the listeners, who understood almost nothing of the sermons, reacted by ridiculing them and staying away, but after about a year, in the winter of 1844-45, premonitions of a revival began to appear. Laestadius says that certain parables of the Saviour began to have a “strange effect on the hearts of the listeners.” They could not dislodge the figurative language from their minds. Laestadius explains: “One person recounted this parable and another person that one to the folks at home. People laughed and pondered what all this could mean. Finally, some of them became troubled without knowing why. Mysterious tremors shook the whole body. The heart began to feel tender, hard or swollen. Some began to come to the parsonage after services to seek advice and enlightenment in spiritual matters. Never before had a spiritually troubled soul come to the pastor to request enlightenment and comfort.”

Laestadius proceeded cautiously with these “lost sheep.” He continues: “Almost timid and inexperienced in the proper tending of sheep, I explained a number of Bible passages that described the condition of their souls, assuring them that the Holy Spirit had begun his work in their hearts and telling them that they should diligently examine their hearts in the light of God’s Word and pray to God for grace and help in their spiritual distress. Finally, I added that he who had begun a good work in them would also finish it, etc. I did not dare assure them of God’s grace or the forgiveness of sins, for I felt ashamed and didn’t dare interfere in the work of the Holy Spirit, fearing that I might ruin everything if I were to promote a premature deliverance.” Applying Christ’s parable of the talents (Matthew 25:14-30), Laestadius urged the rare souls who were awakened to talk to their neighbors. People became angry, but, in spite of this, they began to return to church to listen to the sermons. However, as Laestadius says, “no real cries or loud sobs were yet heard in the church, for the Holy Spirit was not yet working and no really contrite heart was found in the whole congregation.”[38]

In the fall of 1845, a woman looked out her window and saw a group of Lapps sitting in a circle in the yard. Strangely, they were not passing around a liquor keg. Instead, one was reading a book and the others were listening. The woman reacted by saying, “Look! Those must be the false prophets who have appeared here in the parish recently.”[39] Finally, after the law, which is our schoolmaster to bring us to Christ (Galatians 3:24), had done its work, the first “signs of grace” appeared, which Laestadius defines as a “voice from heaven, saying, ‘Thy sins are forgiven’ or ‘Today shalt thou be with me in paradise.’ ” On December 5, 1845, a Lapp woman, identified by tradition as Pekka Piltto’s second wife, Margareta, became the first person to experience grace. This woman, who had long suffered under the law, “jumped high above the ground for joy,” and at the same time, an earthquake occurred. Laestadius writes: “I was sitting at home with Knoblock, the vaccinator, who may yet recall the earthquake, which covered a radius of about 60 miles, and since I was keeping a weather log at the time, I made an entry of ‘earthquake.’ But it was only afterward that I was informed that the Lapp woman had found grace the same moment the earthquake was felt.”

Laestadius

continues: “This sign of grace, which the doubting woman was the first to

experience, now became a sacred goal for all who were awakened but had not yet

received grace, an infinitely great and lofty goal, which all who are troubled

in spirit should seek.”[40]

It was not long before it became quite evident that others were also

experiencing grace. The same winter the effects of grace became visible in the

form of emotional outbursts. These phenomena are referred to in Finnish as liikutuksia, a term equivalent to the

Swedish rörelser, meaning motions,

movements, agitation, excitement, etc. People shrieked and screamed, rose and

embraced one another, swung their arms, jumped, spun in circles, danced and fell

in heaps on the floor or even in snowbanks.[41]

The district magistrate, H. W. Hackzell, who witnessed these

phenomena in church in 1851, described them as something that is not ordinarily

seen, “even when visiting an insane asylum.” He said that, though he had an

ideal spot and Laestadius spoke in a loud voice, it was impossible to hear the

sermon.[42]

In an 1857 letter

to the Hernösand Consistory, Laestadius gives the reasons for these outbursts:

“If the lightning of

In an 1858 letter to the well-known pastor and temperance leader Peter Wieselgren, Laestadius again describes liikutuksia: “In their ecstatic state, some come at a flying pace and jostle me roughly, so that at times I have to guard my eyes and ears. When they have calmed down after perhaps a quarter of an hour, they show clear insight into the order of grace, based on real experience, and a knowledge of God’s Word that is surprising. Thus they have an understanding that is as clear as their feelings are intense. While they fly high over the earth with wings of faith, I stand with my big intellect and insensitive heart, like a bump on a log, unable to respond to their expressions of love, for only a few flashes strike my heart, which is hardened by self-righteousness.”[44]

The mood that existed at the beginning of the revival is described in the memoirs of Anders Baer, a Lapp who had journeyed from Kautokeino, Norway, to hear the preaching of Laestadius: “We stayed in the Pastor’s servants’ quarters during the holidays, and on each of the four days of the Easter season we were in church twice, morning and afternoon, for Laestadius preached in the morning and in the afternoon in Finnish and Lappish. I witnessed something remarkable during the whole Easter season when Laestadius preached in church. The whole congregation would sigh heavily and weep from time to time, but the more the congregation sighed and wept, the more Laestadius raised and altered his voice. And when the congregation was quiet again and had ceased weeping and sighing, Laestadius would also lower his voice and speak slowly, to soothe and comfort them, so that they no longer would fear as much as before, for God is merciful to all penitent sinners for Christ’s sake. Tears would also run from Laestadius’ own eyes when he preached in church.”

Baer then describes the mood that existed after services: “It was not enough that Laestadius preached in church twice each day during the Easter season, but he would spend the evenings in his quarters, speaking of conversion and awakening, especially with his own parishioners. I would also go there to watch and listen, but the Pastor’s quarters were so filled with people every evening that it was almost impossible to find even an inch of space. Some would sit there, some would stand, and some would go in and out. I did not speak at all with the Pastor about conversion. The people who had been in the Pastor’s quarters earlier in the evening would ask those who came later to the servants’ quarters, “What else did the Pastor talk about?” And thus the discussion of conversion, awakening and rebirth would last as late as midnight. After Easter, when we were about to return home from Karesuando, those of us from Kautokeino asked, ‘How much do we owe you for the lodging?’ The Pastor answered: ‘Nothing.’ When we thanked him for the lodging and said farewell, he answered, ‘Go in the Lord’s peace?’ ”[45]

Many of the

awakened fell into trances and saw visions. They saw the Saviour weeping over

spiritual

Laestadius held these visions in high regard and even published accounts of them. He valued them, however, only insofar as they were in agreement with the Holy Scriptures, as he says in one of his pamphlets: “I do not find anything in this revelation that is in conflict with the Bible. Therefore, I have had this revelation printed so that it would be of edification to other awakened souls in their precious faith, and perhaps it might also awaken some impenitent souls, although the impenitent indeed do not believe revelations because they do not believe Moses and the prophets.”[47] For Laestadius, these visions had no inherent authority in themselves but were only a reaffirmation of the written Word of God. Thus he says, “That which has now been said about visions may suffice since it is not a question here of a new revelation. For the believer, these revelations are to be viewed as a new confirmation of the old revelation, with which the worldly minded man is not concerned.”[48]

Laestadius also

mentions his own experiences: “At times, bright streaks have been seen hovering

over persons being moved by intense emotion or joy. I have often seen these

bright steaks, flashes or lightnings, but I am unable to decide with certainty

whether they were outside myself or within myself. It seems most credible,

however, that the flashes or lightnings that I saw were within my own heart. On

Christmas Eve of 1847, as I was walking to church and saw the church road

filled with people, my heart was struck by an inner flash or lightning, which I

have often felt on such occasions. It was like a brighter breeze from a higher

world. In other words, the viewing of this mass of people streaming to church

prompted a fleeting sensation that flashed like lightning through my heart and

was followed just as quickly by the thought: Is such a wretch as I to be the

guide of these blind people to eternity? A few seconds later, I saw a great

bright flame streaming from the church roof in Karesuando in a southerly

direction. On the same evening, some members of the congregation saw black

specters fluttering around the burning candles in the chandelier. It appeared

to them that these specters had a great desire to extinguish the candles but

that their efforts were in vain.” Laestadius viewed the “flashes” that he saw

as coming from “

Laestadius had only harsh words for the theologians of his day and their attitude toward the effects of the Word of God. He says, “The genuine Lutherans of our day do not approve of these sensationes internas [internal feelings], which they regard as fanaticism. Thus they have to reject heartfelt contrition and heartfelt grace. For the sake of appearance, our rationalistic theologians have allowed the doctrine of penitence, repentance and new birth into our Christian textbooks, but this order of grace is so deficient and defective that no one can obtain correct enlightenment from it regarding matters related to true conversion and rebirth. Moreover, according to them, only gross sinners need to be contrite over their sins. Refined and noble offenders do not have to confess to anyone. They usually say, ‘It’s no one’s business how I live. I am the one who must answer for my deeds.’ ”[50]

Laestadius’

criticism was not limited to the religious establishment of his day but also

included contemporary revivalists. In 1845, Fredrik Hedberg, the leader of the evangelicals (evankelist), published the

book Pietism och Christendom, in

which he rejected the doctrine of Jacob Spener and the German Pietists of the

seventeenth century, who called for true penitence and stressed the good works

that flow from faith. Laestadius, in his main work, Dårhushjonet, which was not published in entirety until nearly a

century after his death, defends the Pietists and says of Hedberg, “Except for

faith, which he insists on with all his might, the author of this little book

appears to have forgotten how the new man was born and how he is sustained and

kept alive.” Laestadius admits that Hedberg had “effected much good” when he

was regarded as a fanatic by the Finnish authorities and was “banished” by

these “inquisitors” to

The awakenists (herännäiset) of the Savo

region of

By the end of 1847, the whole Karesuando area was in revival. People confessed their sins and returned stolen property, either to the rightful owners or to their heirs. Feuding neighbors were reconciled. Liquor traders poured their liquor on the ground, and taverns were closed for lack of business. In an 1848 report, District Magistrate Hackzell writes that the peasants, instead of smuggling and distributing large quantities of liquor, as they had done previously, now ordered and disseminated large numbers of religious books. Sundays, which had been spent in drunkenness and fighting, were now spent in studying books and seeking spiritual enlightenment. In a report published a year later, Hackzell writes: “Anyone who is familiar with the Lapps and their irresistible lust for hard liquor and strong drink and has seen the liquor trade and how it has been used by the settlers and other swindlers to cheat and strip them of everything they own and has witnessed the drunkenness of the Lapps and heard them shouting and chanting their joiks at fairs and other gatherings can only be highly amazed at the change that has occurred in them, when now on such occasions he sees them all sober and as quiet and reserved as though gathered in a churchyard to enter the church.” It is also pointed out in the report that if a traveler were to want a drink with his meal he would have to have his own bottle and drink secretly to avoid rebuke. By 1849, according to the statistics in this report, criminal cases had entirely ceased to exist and illegitimate children were no longer born. In an 1850 report, Hackzell writes that granaries and storehouses could have been left unlocked if there had been no threat of theft by persons from other areas.[55]

As early as the

winter of 1847, Laestadius made efforts to spread the revival to other

localities. The first person to be sent to another community was Pekka Piltto,

who was now not only temperate but also awakened. Piltto went to Soppero and

other villages, discussing Christianity from house to house. Later in the year,

Laestadius decided to send out Juhani Raattamaa’s brother Pekka, a converted

drunk, who first had to be taught to read. Lay preaching being banned by the

Conventicle Edict, Raattamaa and the missionaries who followed him were sent

out as representatives of a temperance society founded by Laestadius. They

carried letters of recommendation and written sermons, which they read to

listeners in various communities. At first, the men were received with

contempt, anger and violence and were often driven out of town, but eventually

the Word took root and the revival began to spread to other areas of

Laestadius now

submitted a request to the Swedish Missionary Society to sponsor the

establishment of a school for Lapp children. The society was favorably disposed

after two of its representatives visited the area in 1847. In September,

however, Laestadius wrote a letter to G. T. Keyser, the most influential figure

in the society, criticizing the articles in the society’s periodical, Missions-Tidningen, edited by the

well-known lay religious leader Carl Rosenius, and other literature of the

society: “If I were permitted to voice a criticism of the missionary society’s

editorial policy for its books and Missions-Tidningen,

it would be that the person who writes the main articles appears to pussyfoot

too much with the world. The reason for this may be that the society consists

of heterogeneous elements. Dead and living faith are combined in it, and in

this mix, living faith appears to have more respect for dead faith than dead

faith has for living faith.” In the same letter, Laestadius also criticizes a

booklet in which the society, reviewing its history, ignores the key role

played in its establishment by the Methodist George Scott, who, bitterly hated

by orthodox Lutherans, had been expelled from

Juhani Raattamaa, who had previously taught confirmation classes, became the first teacher of the new school. According to Laestadius, adults became curious about this “strange school, where children were said to be going crazy,” where “some suffered pangs of conscience and others jumped for joy.” Visiting this school, they heard Raattamaa read Laestadius’ sermons and explain Bible texts that he had selected for reading. Some left angry but others remained at the school late into the night.[57] A visitor has left an account of what he saw there: “The children sit there all day long, learning spelling and memorization. The more advanced ones read God’s Holy Word clearly and loudly from the Bible, which Raattamaa explains in a manner that is so simple and understandable to children that they listen with the greatest attention and desire. And the children indeed demonstrate an unusually good knowledge and understanding of the basic truths of Christianity. . . . Adults who have not had any previous instruction have also become anxious to learn to read and understand God’s Word. Raattamaa gathers these persons into his schoolroom during recesses, teaching them not only to read but also to understand the doctrine of Christianity. When he explains the Holy Scriptures or speaks in other ways about the doctrine of salvation, it is done in a manner that is so easily understood and amiable that the attention of the listeners remains constantly fixed on him. His neighbors say that they do not know when he sleeps, for he spends the nights in ‘conversations’ and instruction with those, both old and young, who do not have the opportunity to meet him during the day. He begins and ends his school each day with a religious service that includes singing, reading and warnings for the people.”[58] As a result of Raattaamaa’s work, in less than a year the revival was as strong in Jukkasjärvi as in Karesuando.

In August 1848, Laestadius won the election for pastor of Pajala, which, from a financial and material standpoint, was preferable to serving in Karesuando. The results of the election were contested, however, by one of the other two candidates. Laestadius had clearly received more votes than the others, but the winner was not determined by a simple majority. The election was based on a system of property ownership weighted in favor of the large Swedish landowners, who consistently opposed revival. In reply to a letter, dated October 23, 1848, from friends in Pajala Parish who were concerned over the election, Laestadius said that he would not have applied for the position if he did not have so many children, so little time to teach them and insufficient income to hire a teacher. He wrote: “If Sjöding, as is likely, now wins the position of pastor of Pajala by taking legal action, I will have to be content. I must not follow the custom of impenitent pastors, who, through craftiness and litigation, gain larger parishes. If God has determined that I am to be a teacher in Pajala, I will have to come when appointed. If, however, God has not so provided, both you and I must remain content. I think that the pastor who has now begun to take legal steps will eventually regret it when he finds himself among ants. For we know that a snake is nowhere in such distress as on an anthill. I do not doubt that Christianity will spread regardless of how strongly it is opposed by an impenitent pastor, and we may well suppose that Sjöding has not raised his complaint for the sake of Christianity but for worldly gain.”[59] The church authorities in Hernösand rejected the complaint because the documentation was incomplete, and so Laestadius acquired the new position in March 1849.

The election

victory did not mean that the revival had already spread to Pajala to any

significant degree. Pajala, located south of Karesuando, on the

Signs of

persecution began to appear even before Laestadius’ arrival. In the letter that

Laestadius received from his friends in Pajala Parish, they wrote: “The

Heavenly Parent, out of his grace, poured great joy on this village, which

happened on the eighteenth Sunday after Trinity, during prayer, and it made the

children of the world so angry that they are beginning to complain to the

government and to take legal action.”[60]

Soon after his arrival, false stories began to circulate about Laestadius. It

was said that he was a greedy hypocrite, that he pocketed all the valuables

donated to the school (which was now in the

The tone of District Magistrate Hackzell’s reports now changed. In a report published in the press in May 1851, he complained that the level of debt had increased and that people were neglecting their work, spending weeks on end at school. According to Hackzell, those who had previously wasted their money on liquor were now spending even more on coffee. He also complained about the liikutuksia in Pajala, saying that the “devotion” of the listeners was disturbed by such outbursts. As for the situation in Karesuando, Hackzell said that he could not make any statement because during his visit the pastor there was “indisposed” and unable to conduct services. In his rebuttal, published in the same newspaper, Laestadius pointed out that the reason the pastor of his former parish could not conduct services was that he was lying drunk in the vestry, which Hackzell should have reported instead of complaining about the involuntary outbursts.[62]

Those who warned

their neighbors of the danger of dying unrepentant were threatened and even

assaulted. In the spring of 1850, for example, a man by the name of Juho

Aaronpoika became enraged while hearing a visitor discuss Christianity. He led

the visitor out of the house by the collar, beating him repeatedly with an axe

handle and breaking the arm with which the victim tried to shield his head.

Though fined heavily for this, again in the fall of 1851, enraged at hearing

the Bible being read in the house after waking up one morning, he beat up a

visitor and threw a shovel after him as he ran off through the yard. Once, when

Laestadius was at the door, preparing to leave the house after visiting Juho

Aaronpoika’s sick mother, Juho suddenly jumped out of bed and gave such a hard

blow to the Pastor’s ear that his pipe flew out of his mouth.[63]

Those who preached

repentance were even summoned to court. In February 1850, for example, one

Antti Lahti was accused of having told an unconverted man that many of his kind

were in hell. In his statement to the court,

Complaints were

raised against Laestadius within a year of his arrival in Pajala. In an article

in the periodical Ens Ropandes Röst i

Öknen, which he began publishing in 1852, he reviews some of the charges.

He says that one complaint was prepared by a former constable by the name of

Lars Johan Bucht, whom he accuses of having recently fled from Luleå to

Another complaint, described in the same article, was raised by Juho Vänkkö, the church sexton, who charged that Laestadius had refused to church his stepdaughter after the girl had given birth to an illegitimate child. The complaint, written on behalf of the parents by “a certain liquor trader,” was sent to the provincial pastor, who forwarded it to the Consistory. In this case too, an explanation was demanded. Laestadius writes, in his article, that he had asked to have a talk with the girl before accepting her confession, and in view of the insolent attitude that she displayed during the meeting, the ritual was postponed. Laestadius points out that church rules require that persons to be churched manifest true penitence. Laestadius was strongly opposed to the leniency of other pastors, who paid no heed to the spiritual condition of those to whom they proclaimed absolution. He writes: “The pastor rushes forward instead, as though playing blindman’s buff, and absolves a sinner without taking his spiritual condition into consideration. Thus he uses the keys of the kingdom of heaven in somewhat the same manner in which the prince of the bottomless pit uses his keys to the gate of hell. He indeed lets all the goats and scorpions into his kingdom without examining whether they are repentant or not.”[66]

Laestadius

maintained that he was not legally obligated to reply to the charges made

against him because the complaints had not been signed by the persons who had

actually written them. However, in flagrant violation of the law, the

Consistory again demanded that Laestadius explain his actions. In a letter

dated January 4, 1850, Laestadius repeated his position, commenting that

Muodoslompolo had subsequently declared in the presence of witnesses that he

had neither requested nor signed the complaint made in his name. Most likely,

Muodoslompolo had reconsidered the matter in the light of the travel expenses

involved in pursuing the case. At any rate, Laestadius felt he should not have

to reply to anonymous complaints. He said that he suspected that the complaint

had been written “under the influence of an infernal passion, which revealed

itself in the form of spiritual hatred, the real cause of all religious

persecutions,” and that the author, “though a fugitive from justice, felt

compelled, as a genuine Lutheran and with a brain stimulated by orthodox gall,

to defend the purity of Lutheran doctrine, which he imagined to be in danger of

being eradicated by the repentance sermons of the readers.” As for the case of the unchurched girl, Laestadius

wrote: “Forasmuch as it can be proven that the guardian, Vänkkö, did not, of

his own free will, give his consent to the writing of the complaint but that

other individuals had coaxed and inveigled him into it and had even made

threats, which they intended to carry out unless he yielded to the wishes of

those whose tender consciences were highly troubled by my temperance sermons,

as being the worst heresy, whereby the common people are beguiled away from

pure and genuine Lutheranism, clarified in a liquor still and in alcoholic

beverages, I have prepared this appeal for the purpose of forcing slippery and

elusive snakes, who would rather lurk in darkness, to creep out into the

daylight. The fact is that all members of the leech family are greatly troubled

by the bitter salt of truth. ‘But if the salt have lost his savour, wherewith

shall it be salted’ [Matthew 5:13]? If the salt in the

The Consistory

insisted on receiving explanations and decided to formally reprimand Laestadius

for his disobedience and the “indecent and improper expressions” in his letter.[68]

He was given only thirty days to appeal the decision despite the fact that the

mail was collected only twice monthly from Pajala. His legal representative in

Laestadius now sent the explanations to the Consistory, and they were accepted. As for the unchurched girl, she was churched by another pastor and soon gave birth to another illegitimate child. In the account given in his periodical, Laestadius mentions this, adding that it “is no longer any secret” that “she has even committed incest.”[69] Laestadius later retracted this statement, but it was to no avail, for he was eventually fined the rather hefty sum of 300 rix-dollars for making it. Although the girl had made the statement in the presence of witnesses, it could not be proven in court. It should be pointed out, in order to make the size of the fine better understood, that it is known that the Pastor’s basic annual salary in Karesuando had been about 300 rix-dollars. However, this figure does not include other benefits or income. In Pajala, where his salary was higher, he reported an income of 1,046 rix-dollars in 1856 and 2,667 rix-dollars in 1858.[70] This fine may be one reason why Laestadius ceased publication of his periodical in 1854, for in a letter written in 1860 he complained that he was still suffering financially from the case and was unable to finance publication of Dårhushjonet.[71]

At about the same

time, the Finnish authorities began to take action against those who

experienced liikutuksia in church. In

an 1857 letter, Laestadius tells how two women of Ylitornio were imprisoned in

Certain dramatic

events now occurred in

Hvoslev then tells how, in the winter of 1849-50, some of the Lapps began to declare themselves “holy and righteous.” From this time on, he says, traits such as pride and hypocrisy became increasingly apparent. The inclination to consult God’s Word ended and “the Spirit, the Spirit” became the slogan. The following winter a real rivalry emerged among them as to who was the greatest -- who had the greater revelations and experiences of grace. Pride drove them to assert finally that they were resurrected, without flesh, and even that they were Christ. From this time on, according Hvoslev, “unrest and confusion began to spread in the congregation.”[74]

Laestadius met some of the Kautokeino converts in Karesuando, during a visit that he made to his former parish in the winter of 1851-52, before the notorious events had occurred, but they were so “confused and deranged” that he couldn’t exchange a reasonable word with them.[75] He noted that “their complexion was dark, as was their countenance; they had a white froth in their mouths and they spit often.”[76] In an article written after the Kautokeino events, he describes their doctrine: “These words of Luther, “I am Christ,’[77] could easily give the ignorant Kautokeino Lapps a basis for self-deification, and I believe I found this arrogance in those few with whom I spoke in Karesuando last winter, 1852, though they were not leaders of the sect. They asserted not only that they were equal with Christ but even that they were pure spirits and hence sinless. They said that they had experienced the ten stages of Christ’s humiliation and exaltation. And since they were now gods, they considered themselves above the Bible, which they called the Bible of the impenitent. The result was that the reasonable readers were unable to oppose the fanatical ones, for when Bible passages were quoted to refute these heretical notions, the fanatical ones would reply, ‘We are above the Bible; we can now write a better Bible ourselves.’ ”[78] Laestadius mentions that in a letter sent to Bishop D. B. Juell -- who later became his accuser -- he had rejected this “fanaticism” even before the Kautokeino tragedy.[79]

Stockfleth’s journal also contains statements made by the fanatics, based on notes taken at their insistence during conversations he had held with them: “We are come to bring strife. Where we are there can be no peace. To fear God one must sin, for only one who sins can fear; but we do not fear God, for those who have the Spirit cannot sin. We are God’s limbs, and God cannot punish or judge his own limbs; hence, God cannot judge us. We are dead and so we cannot die. There are spiritual bodies and fleshly bodies; we do not have fleshly or physical bodies but spiritual bodies. We are on the new earth. We are spiritual, holy and righteous. We are the Bible, the New Testament, Sinai. Our body is the law; consequently, we have the right to judge. We are God the Father, Son and Spirit. The Son has lost his power, which is now with us. The Spirit in us has the power to kill. The pastor that does not deny that he has flesh is consequently mortal and belongs to the devil. We do not have flesh; the flesh has been killed; we will no longer die, for we have already died once. We can see inside all men and determine whether they are spiritual or fleshly. Christ said, ‘Get thee behind me, Satan.’ Hence, the spiritual ones have the right to call you devils and Satan and to treat you as such. When you say, ‘Our Father which art in heaven,’ you are lying. You should say, ‘Our Father which art in hell,’ for as long as you have not been converted to us spiritual ones, the devil is the father to whom you pray. Children should curse their parents so that the curse would return from generation to generation right back to our first parents. Those who do not become free of sin in this world will not enter the kingdom of heaven. We have not received the Spirit through reading the Bible but through conversion and prayer. We spiritual ones in Kautokeino can say of ourselves, ‘By virtue of the Spirit we are true God and by virtue of our human nature we are true man.’ It is not fitting to be obedient or to pay taxes to unspiritual and unconverted authorities. ‘If you, who are supposed to be our teacher, were really filled with the Spirit, as we are,’ they told me at the general conference, ‘you would not allow anyone who did not have the spirit, as you do, to be in peace and remain alive. This is what we do, and this is what we will do in the future.’ They wanted to disturb the complacency of the sinner, and no one was supposed to hinder them. ‘When the power to curse comes over me, I curse, etc.’ ”[80]

Kautokeino did not have a permanent pastor until Hvoslev, who was appointed to the position in November 1851, arrived there in 1852. The congregation had been served from time to time by Pastor Zetlitz, who observed the revival in Kautokeino when he arrived there in February 1849, after an absence of nearly a year due to illness. During the three weeks that he spent there, he made a note in the church records that a “religious fanaticism had spread among the common people with surprising speed.” It was characterized by anguish over individual sins and liikutuksia, of which he did not approve. He classified the entire movement as one in which “self-justification outside of Christ was preached.”[81]

On March 18, 1850, Bishop Juell arrived to carry out an inspection. He presented his impression of the revival in a letter, dated April 17, 1850, to the Department of Ecclesiastical Affairs, in which he says that it started at the beginning of 1848 as the result of a visit by missionaries and that it was legalistic. He says that the preachers stressed the need for penitence and repentance and felt that people could “reform, refrain from sin, fulfill God’s law and become perfect children of God through man’s own efforts and that some had already succeeded and were, therefore, already viewed as holy, pure, etc.”[82]

In a letter, dated May 8, 1850, to the same authorities, Juell mentions the moral improvement in the lives of the Lapps and expresses the hope that the revival, in spite of its shortcomings, would become a blessing. He regrets that Zetlitz had adopted a negative attitude from the beginning and conveys the request of the people that a pastor with a knowledge of Lappish remain with them the whole winter. He adds, however, that despite the fact that all those with whom he spoke “did not want to know anything other than Jesus Christ and him crucified” and said that “all their comfort was God’s unmerited grace through him,” they were “too inclined to lay undue emphasis on their works and, therefore, to place an old patch on a new garment,” and “rely on and wait for the emotional efforts of grace in their hearts instead of the grace that the Lord has promised through his means of grace.” He then adds, “I tried to open their eyes to this error, which they were not unwilling to recognize. There were many who combined a simple faith with a clear Evangelical Lutheran understanding of saving truth.”[83]

On September 16,

1851, the Bishop sent a request to Stockfleth, who knew Lappish, to visit

Kautokeino, and the latter arrived on the night of October 21 after a long and

difficult journey by land and water. In his diary, he says that even before

landing he heard the Lapps engaging in a noisy uproar in front of the house of

the merchant Ruth, with whom they were upset because of his refusal to end his

liquor trade. Stockfleth says that he heard them uttering “wild cries about

conversion, accompanied by curses and threats,” but by the time he actually

arrived the demonstrators had left. He says that their violence had increased

recently, that people who refused to repent had been whipped and that the

fanatics had broken into homes, including that of Ruth, where a woman had torn

the merchant’s wife’s dress to shreds. Stockfleth spent the night with Ruth,

and the next morning he went to meet the Lapps alone in the sexton’s house,

where they were gathered. He entered and greeted them but did not receive a

response. Two men and a woman were hopping about, condemning all the

unconverted to hell, and the others were lying on the floor. According to

Stockfleth, when he was finally recognized, the jumpers redoubled their

movements, becoming even louder, and he kept them from pressing against him by

striking them a couple of times with his walking stick. The other Lapps now

became agitated and, with frenzied expressions, started hopping about, flinging

their arms up and down and cursing the unconverted. Stockfleth approached the

sexton, Mathis Hetta, who was lying fully clothed on a bed and acting as excited

as the others, but did not receive a response. After observing the scene

awhile, he went out but turned again to watch them jumping and shouting

hoarsely in the yard. Finally, shaking his head, he left.[84]

Laestadius also gives an account of

Stockfleth’s arrival, which he had heard from someone who had spoken with the

sexton. According to Laestadius, Stockfleth, arriving unannounced “one fine

morning,” entered the house and uttered a greeting. The sexton, half awake,

recognized Stockfleth, but since he had heard that he was in Christiania (the

former name of

Stockfleth, assuming pastoral duties, began to take drastic measures. On the Sunday after his arrival, he announced that he would not admit anyone to confession or Communion without an examination. When the Lapps tried to force their way into his house on October 29, after he had kicked them out during a conversation in which one of their leaders, Rasmus Spein, demanded to be recognized “not as Christ but higher than Christ,” Stockflesh summoned the police from Alta. On November 1, the fanatics called for a “general conference” with Stockfleth. Six of the leaders and four men and two women then met with him in a large room. Opening the meeting solemnly and politely, they explained their doctrine at length. One of them told of two visions or revelations, which he had experienced after three days of prayer in the woods. Christ had appeared to him in a shining form and had delivered to him the authority to act as a judge. After a discussion that lasted one and a half hours, they left with their usual “cries and threats,” not having succeeded in convincing Stockfleth of the truth of their doctrine.[86]

On November 9, the police, having arrived from Alta, arrested Spein during an uproar in church in which he had gone to the pulpit to condemn the Pastor. The local constable, who did not make any move to assist the police, was later removed from his position, which was given to the infamous Bucht, the fugitive constable and enemy of the revival, who was now living with the merchant Ruth. Other arrests were made on various occasions until as many as 22 Lapps were arrested. On February 9, Bishop Juell arrived in Kautokeino at Stockfleth’s request, followed by other officials. A church inspection and legal proceedings were held. The Lapps were found guilty; some confessed and were forgiven, but others received prison sentences. As for Spein, he was sent to Christiania Penitentiary, where efforts were made to teach and correct him. He resisted for a whole year but then feel ill, and on his deathbed he finally asked for forgiveness from Stockfleth, who happened to be present. Stockfleth reviewed the articles of the Creed with him, prayed with and for him, pronounced absolution, and gave him the Lord’s Supper and the benediction. A few hours later the prisoner was dead.[87]

After leaving Kautokeino, Bishop Juell sent a letter, dated March 5, 1852, to the Department of Ecclesiastical Affairs, in which he said that the movement among the Kautokeino Lapps was the result of “concern over the salvation of souls” and that “thus it was effected by God’s Spirit.” He mentioned the unfortunate course of events, saying that the more the Lapps had to be without guidance and enlightenment of the Word of God from teachers who knew their language, the more they accepted every movement of their imagination and mind as the direct effect of the Spirit. He blamed this state of affairs, at least in part, on the “influence exercised by the terroristic and crudely worded law sermons printed in the Finnish language,” in which both spiritual and secular authorities were attacked.[88]

On April 7, 1852, Hvoslev arrived in Kautokeino as pastor, and Stockfleth left on April 20. The situation remained calm during the entire summer. However, the authorities continued to provoke the Lapps in various ways. Some of them were still denied the Lord’s Supper because of inadequate confession of sin. Bucht, who is said to have physically abused them, made several attempts to arrest a Lapp woman who had not yet served her sentence, but since her village moved from place to place and she adamantly refused to surrender, his efforts failed. As for the Lapps who had already served their sentences, they returned home to find the authorities planning to seize all their possessions to recover court costs. On one occasion, according to Laestadius, the vivid imaginations of the sensitive Lapps became inflamed when someone placed chains and shackles in front of the church during services. One of them cried out, “Now Stephen’s faith will be tried!”[89]

On October 30, Hvoslev heard that the “spiritual ones” were traveling to other villages to convert people, particularly women, and that they had begun to live in an unrestrained and wild manner. Although he did not expect violence, he planned to speak with Bucht on November 7 about sending to Alta for help in dealing with the situation. However, when that day dawned, the final drama began to unfold. Aslak Hetta, the leader, had dreamed that in a struggle with an opponent he had overcome him and bit off his nose. In another dream he had cast an opponent with whom he had been struggling into a well. Only one stage of Christ’s exaltation remained -- that of judging the quick and the dead. At Aslak’s word, the Lapps in his village, 30 adults and 19 children, began moving toward Kautokeino in a long line of sleds, one loaded with birch switches. Along the way, during the night, they whipped the unrepentant and forced them to join the procession. On the morning of November 8, they arrived at Ruth’s house, where Ruth and Bucht were approached in the yard. Aslak shouted, “Repent, you devil of a constable!” and knocked Bucht down with a club. Aslak then cast himself on top of him, bit off his nose and, taking the constable’s knife, stabbed him under the left arm. The Lapps then beat both Bucht and Ruth unconscious, but Bucht, regaining consciousness, tried to escape. Aslak overtook him, however, and stabbed him again. Though half dead, he made it to the attic, where he lived, but there Lars Hetta, a brother of Aslak, finished him off.[90]

Alerted by Ruth’s

wife, Pastor Hvoslev rushed from the parsonage to find Ruth apparently dead

already from knife wounds, his body still being abused by raving women. Aslak

initially intended to cast the body into a well but changed his mind and

ordered that it be left where it was as a “terror to

In the late

afternoon, help finally arrived from the

Laestadius now faced

a storm of criticism, for the events in Kautokeino caused a sensation

throughout

After the murders,

Juell sent a complaint to the Norwegian Department of Ecclesiastical Affairs in

which he laid responsibility for the events on Laestadius, as the originator of

the movement, and recommended that he be placed under “supervision.”[93]

At that time,

In the midst of the turmoil, Carl Sohlberg, Constable Israel Stenudd, F. V. Forsström (a merchant whose liquor trade had been ruined by the revival) and four peasants submitted a complaint to the Consistory against Laestadius, in which they requested a bishop’s inspection. It was charged, among other things, that Laestadius had collected illegal fees, that he used indecent expressions in his sermons and that the animalistic shrieking and shouting in church disturbed the solemnity of the service and prevented people from hearing the sermon. Bishop Israel Bergman came to conduct the inspection in July 1853. After finding that financial matters were in order, the issue of indecent language was taken up. The Bishop asked that the offensive words be repeated in front of the congregation. However, no one dared repeat them in the presence of the Bishop until Sohlberg finally uttered them: “Chaste whores want to be churched while the filthiness of their whoredom is still dripping from their rear ends onto the church floor.” However, this statement, which was typical of the Pastor’s preaching style, could not be used against him, mainly because the accusers could not tell on which Sunday it had been made. As for the disturbances in church, the accusers said that these incidents disturbed their devotion. As a result, the Bishop ordered that two sermons be given, the first one for those who are offended by the liikutuksia and the second one for those who are likely to experience them. Laestadius asked, “But if someone gets pangs of conscience during the first sermon, though he has not had them previously, what is to be done with such a person?” The Bishop answered, “Such a person may be removed from the church.” During the inspection, the Constable noted that in Laestadius’ doctrine there is much that is in conflict with Lutheran doctrine, such as public confession of sin. “Public confession of sin?” asked the Bishop, “is that in conflict with Lutheran doctrine?” The Constable could not explain his statement, and the accusation was dismissed. The outcome of the inspection was a great relief to those who were awakened. Laestadius says that some of them felt great love for the Bishop and even embraced him before he left.[95]

Later the same year, Bishop Bergman also submitted a statement to the King in response to Juell’s complaint, which had been forwarded to him. He took the position that Laestadius, though the originator of the revival in both Swedish Lapland and Kautokeino, could not be viewed as legally or morally responsible for the Kautokeino events. In a letter to Archbishop Henrik Reuterdahl, the Bishop also expressed a fear that Laestadius might lend his support to the separatist movement: “Careful thought should be given to any action that is taken before making any direct or indirect charges against Laestadius for that which has taken place. Otherwise, he can easily become a new and influential voice crying out for dissolution of the Church.”[96] The King, having received Bergman’s statement, decided that there was no reason to take any action against Laestadius or his doctrine. However, Bergman was asked to “keep a close watch in the future on the manner in which Laestadius carried out his duties so that no cause would be given for anyone to disturb the peace and order that should prevail in Christian society.”[97]

Not long

afterward, the Consistory demanded an explanation from Laestadius for language

used in pamphlets containing two visions and three sermons. The King had

received these pamphlets from

After receiving this explanation, the Consistory prepared a written warning, which was formally presented to Laestadius in the presence of other pastors. In this warning, dated October 11, 1854, the Consistory expressed its disapproval of the manner in which divine truth had been treated and presented in the printed sermons and of the efforts of Laestadius to use the Bible and Luther to support the use of expressions that any unerring critic should consider violations of the sanctity of the Word of God and the temple sanctified for his service. The Consistory did not consider it proper for a teacher of religion and a Lutheran pastor to disseminate visions whose divine origin was uncertain and appeared instead to be the product of a grossly sensuous view of Christianity and an overactive imagination.[99]

More trouble emerged when a new governor, after visiting Pajala, asked the constable to submit a report on the situation existing there. In his report, the constable discussed the noisy meetings, which lasted for weeks, claiming that people gave all their gold and silver to the school, that some were leading an idle life and that the parishioners were becoming impoverished. The governor submitted it to the Consistory, together with other documents, containing allegations regarding the illegal removal of timber from public lands for use in the construction of a school in Muonio. According to Laestadius, the timber consisted of one scrub pine.[100] However, an investigation was conducted in the form of a meeting held on January 17, 1858, at which Sohlberg, Forsström and the enemies of the revival presented their case and the other side defended itself. The pastor who conducted the investigation submitted a report in which he reviewed the arguments, adding that uneducated missionaries had been sent by Laestadius to run schools in Övertorneå.[101] Without giving Laestadius an opportunity to respond, the Consistory, in a letter, dated March 24, 1858, warned him about sending unqualified individuals to conduct meetings in other parishes.[102] In his reply, dated April 23, 1858, Laestadius denied that he had sent any missionaries to Övertorneå, saying that the residents there had appointed instructors to teach their children because the official teacher did not visit the more distant villages of the parish. He also asked to be allowed in the future to avail himself of his right as a member of a constitutional society to express himself in regard to unjustified accusations.[103] Later in the year, the governor tried to have the separate service for the awakened abolished. An explanation was requested of Laestadius, which he submitted in September. Bishop Bergman saw no reason to make any changes to the system he had set up. The Consistory agreed, and no further action was taken.[104]

At about the same time, some who experienced liikutuksia in church were brought before Swedish courts. In September 1858, for example, the case of three women who had caused disturbances in church after receiving communion was taken up in Haparanda. Witnesses were called to state their opinion as to whether the actions were voluntary or not. When the awakened witnesses testified that they were the work of the Holy Spirit, the judge said, “They could just as well be of the devil.” The statement of a doctor who was clearly prejudiced against the revival was obtained, and though it presented the view that the actions were voluntary, the judge did not find the women guilty but transferred the case to another court.[105] In another case, a young woman of Övertorneå who was working in Nederkalix, where liikutuksia had not been witnessed previously, was charged with having danced and uttered loud noises after Holy Communion. When her case came to court in May 1859, the judge found her guilty without even requesting a medical statement, but she was acquitted in a higher court.[106] In some cases, individuals who appeared in court for having disrupted services could no more easily control their emotions in court than in church and had to be removed from the courtroom.[107]

At least as early

as 1857, Laestadius began experiencing chest pains, shortness of breath and

memory lapses. His eyesight also grew so weak that he could hardly read. In the